In one beautifully and artistically composed page with attractive photographs, Ladera Crier presented:

How a Pattern on the Sidewalk Inspired a Very Special Book “ Seeing Hearts” by Dani Chammas

One day, about four years ago, on what otherwise could have been described an “uneventful” neighborhood walk, the Chamry Sisters ( Zeina 9, Zoe 6. and Sami 4 ) noticed a heart in cement of a sidewalk. Filled with excitement, they all took turns taking pictures of that heart.

Every day since that day, the girls have been searching for hearts throughout the world around them—at home, at school, in nature… some even in Ladera. It is not uncommon for their family activities to be punctuated by the comment, “A heart! I found a heart!” The excitement associated with these moments has persisted through time.

Wanting to share their joy with the world, the girls began collecting pictures of these hidden hearts with the dream of one day using them to create a book to inspire the world. At last “Seeing Hearts” got published and they hope it will MAKE RIPPLES and add Beauty and Fun to our world!

_________________________________________________

Billy was so Inspired, he immediately wrote to the Ladera Crier’s Editors:

Dear Crier Team,

Thank you for publishing another inspiring issue of Ladera Crier. This time I am especially impressed by the three Chamry sisters who co-authored “SEEING HEARTS”. It’s simply MOVING. I like to thank them and encourage them to carry on and MAKE WIDER RIPPLES around the World as they grow older. Since I do not have their email address, will you kindly deliver my message to them, and indeed I thank you for introducing ZZ&S to our Life in Ladera.

Dear, Zena, Zoe, and Sami,

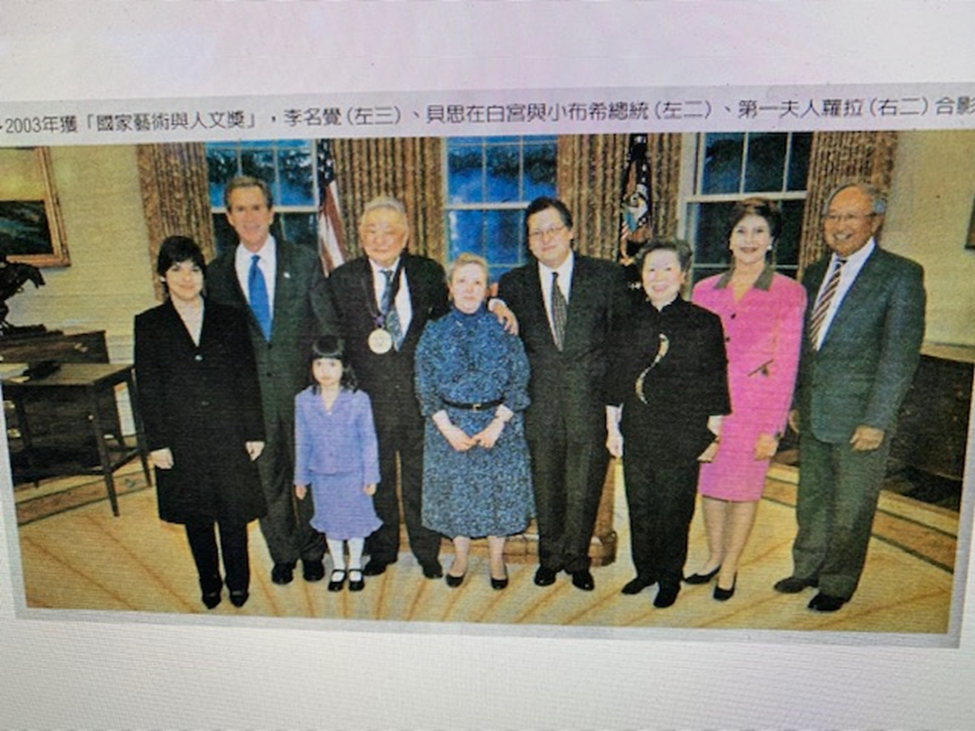

You have added FUN, JOY, and LOVE, into my life in Ladera. This 92 year old Ladera neighbor of yours truly admires what you are doing. I wish you the very best in promoting a rippling effect around this world. I came to America from China when I was 14, and in trying to make Friends in a new country, I worked hard at how to bond with others Heart to Heart. I have made many good friends, and in fact I have kept in touch with many of my old classmates from Phillips Academy Andover and Yale College. Very recently I was mentioned in Yale Alumni Class 1955 news: It noted :

“Billy Lee sends his cheerful news: While seeking the Fountain of Youth

around the world, he accidentally fell into an Ocean of Joy, Beauty, and Love.

Yes they are all around us. Just See, Seek, Savor, and Enjoy with True Heart.”

Cheers, Hope to become your FUN OLD LADERA FRIEND !

Billy Lee- 271 West Floresta Way Portola Valley, Ca. 94028

<https;//friendshipology.net>

Indeed, Billy wishes to introduce The Chamry Sisters and their “Seeing Hearts” book to his good friends at All China’s Women’s Federation and China National Children’s Center in Beijing where years ago Billy conducted “Heart to Heart “ Friendship Connecting between children from US and China via The 1990 Institute. He thinks that Dr. Ashfaq Ishaq , Director of ICAF ( International Child Art Foundation in Washington DC } should know about our amazing Ladera Sisters as well.

_______________________________________________