The author is a neuroscientist, a mediocre tennis player, and a longtime friend of the Lee family. He lives with his wife and son in Potomac, Maryland, where he can often be found chatting up complete strangers to the amusement and/or embarrassment of his family. The ideas expressed within are his alone and do not reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health or the United States Government.

Several years ago, my good friend Gary Lee told me that his father was working on a “friendship project”. I was intrigued. The more I learned about it, the more I thought this was a brilliant and important thing to do. The resultant Friendshipology website contains a variety of enlightening and beautiful essays, many of which describe personal experiences of friendship. This site serves as a wonderful reminder of the value and power of friendship (thank you Billy Lee!). Earlier this year, Billy asked me to contribute an essay to Friendshipology with the seemingly simple suggestion that we might be able to learn something about the nature of friendship from recent advancements in neuroscience. Now, how hard can that be? Just apply what little we know about the seemingly infinite complexities of the brain to understand the infinite complexities of friendship. I have to wonder whether Billy has profoundly overestimated my ability to connect these two topics, or perhaps he is just punishing me for something I did when I was a teenager. Unfortunately, despite all the recent progress in neuroscience, we remain far from a good understanding of the neurobiology of friendship. Nevertheless, Billy’s suggestion has preoccupied me for the last couple of months. What follows are some linking propositions that relate our current thinking about the operations of the mind to some observable features of friendship. I have avoided speculation about the biology of friendship, and at times I have strayed from the science-of-the-mind theme altogether, but I hope the friendly readers of Friendshipology will find these meanderings as interesting and provocative as I do.

As a scientist, my inclination is to start with first principles. I began with the question: What is friendship? I don’t have an easy or definitive answer to this question. The Webster’s Dictionary defines a friend as 1) a person who has a strong liking for and trust in another person or, 2) a person who is not an enemy friend or foe. I think we can all agree that this definition, though not inaccurate, does not remotely capture the nature of friendship. Friendship is a wondrous and multifaceted thing. It can mean different things to different people, friendships are formed and transformed in an infinite number of ways, and yet we use same word to describe them. It’s something that most everyone has experience with, and yet no two friendships are alike. The foundation and the elements that constitute a friendship vary widely, but we all recognize them. The term chemistry is often used to describe the dynamics of a relationship, which is an apt metaphor. However, perhaps friendship can also be understood at a more fundamental level as the product of a universal affiliative force or energy ..let’s call it “friendship chi”. Like gravity, it is omnipresent, it acts on us, we act on it, and it attracts and connects us all. I was thrilled to discover in Stephen Lee’s essay from November 2021 a discussion of the Chinese value of loyalty (Yi Qi) which is described as “a code of conduct between friends or the force/energy leading to such behavior”. It seems the concept of friendship chi is quite ancient!

Now that I have decided that a definition of friendship is a non-starter, let me make attempt to establish some points of contact between what we know about the functions of the mind and what we understand about friendship. While I really like the notion of friendship chi, it’s not my intention to try to connect this concept with the workings of the mind…but I invite the reader to make their own connections. I have organized what follows into brief sections that focus on a few specific functions of the mind that most neuroscientists, cognitive scientists, and psychologists would attribute to the working of the brain. This is not meant to be an authoritative or exhaustive treatment of this topic, far from it, but hopefully it can be a starting point for some future conversation with friends over drinks and a nice meal.

It’s easy to make friends, but hard to get rid of them.

-Mark Twain

Friendship and the Developing Mind

I find it remarkable that the capacity for friendship is evident very early in human development, far before many other cognitive faculties are fully mature. How early? We know that toddlers demonstrate affiliative behaviors towards peers long before language and social skills are fully developed. It seems that our brains are wired for friendship at very early stage. We all have experienced this firsthand, and some of us may have observed this in our own children. Whether there is a genetic component to affiliative behaviors or whether they are learned (probably a bit of both), it is noteworthy that our capacity for friendship may be present long before we are fully toilet trained. This ability to form bonds of friendship early in life speaks to the fundamental and persistent nature of these relationships. These early life friendships are most often defined by motivations that are specific to that tender age. For example, a shared interest in sports, a favorite tv show, or the desire to eat powdered Jello mix straight out of the box. In many instances, and this has been my fortunate experience, these early friendships endure. Of course, friendships evolve and grow with time, but they also serve as a connection to a shared past. Many of the guys within the group of friends from my childhood neighborhood can trace their friendships back to kindergarten (I was a relative latecomer, arriving in the 5th grade). There is also a timelessness that is associated with both the formation and maintenance of friendships. Most of us don’t enter friendships with a mindset that the relationship is finite in time. Friendships don’t expire like a lease on a car. These are, by definition, open-ended engagements. When we think of friends with whom we have lost touch or who have passed away, those friendships exist in our minds in the present tense irrespective of the separation. As we move through life, our friendships serve as a constant in an ever-changing world. The mind continues to develop throughout our lifespan and our social connectedness through friendships is an important part of that continuous developmental process. Indeed, there is ample evidence to suggest that friendships are an important component of overall wellness and a key ingredient of successful aging.

Friendship, Self, and Others

The notion of the self as distinct from others seems natural and, in many ways, is celebrated in western society which places a great value on individualism and individual accomplishments. However, it can be argued that an extreme separation of self from others can be isolating and unhealthy. This may sound familiar to those with a knowledge of eastern philosophy. Buddhism, for example, teaches that an adherence to a strict dualist perspective (self vs others, us vs them, good vs evil, etc) can only lead to delusion and sorrow. I would like to suggest that friendship can be thought of as an antidote to the detrimental consequences of the mind’s polarization of self and other. Friendships can be thought as a privileged and profound connection between minds….and this is accomplished without the internet! There is a cognitive ability that is closely related to the concept of self, it is what psychologists and cognitive scientists refer to as Theory of Mind or ToM. ToM is the ability to attribute mental states, such as beliefs, intents, and emotions to ourselves and, importantly, to others. You can think of it as a kind of mind reading, being aware of one’s one own state of mind and that of another person. It is the stock-in-trade of psychologists and professional poker players. In my experience, some people are better at this than others. It is also my experience (and my wife can surely attest to this) that ToM takes effort and practice. It is a key ingredient of social behavior and a critical component of emotions like love, sympathy, and empathy. Friendships are sustained by an understanding of each other’s mental states. This often takes the shape of words or deeds, but it is a form of sharing. There is a give and take in friendships that has a foundation in a shared understanding of each other’s feelings, interests, aspirations, etc. Friends give and receive in many ways, like a baseball being thrown back and forth between two people (no discussion is complete without a sports analogy). One must be attentive to their playing partner and make the necessary adjustments to keep the game going. If the ball gets dropped, one side must work a bit harder for the game to continue. Friendship, like a good game of catch, requires all those involved to be open to receiving and generous in giving. I have used the act of playing catch figuratively, but it can be a quite literal process for developing and maintaining relationships. Many years ago, my brother-in-law told me of how he would in invite his teenage daughters to toss football around as a method to engage them in conversation and learn more about what was happening in their lives. An ingenious parenting strategy. He has a great relationship with his daughters, who are now wonderful and accomplished adults and who can also throw a football with a nice tight spiral. If you are interested in a more embodied expression of friendship, see my friend Neil Norton’s excellent essay that discusses movement as a means of communicating and connecting.

We are social animals and we thrive through our connections with others. It is the formation of these social connections that reduces the distance and differences among people. An act of friendship is an acknowledgement and an expression of our shared humanity and, just maybe, the mind’s way of breaking down the distinctions of self and other to make us happier and better humans.

Friendship is the most valuable thing a man can have. It’s worth more than money, land, horses, or cattle. It might be the only thing you never forget.

–Blackthorn, 2011

Friendship, Motivation, and Reward

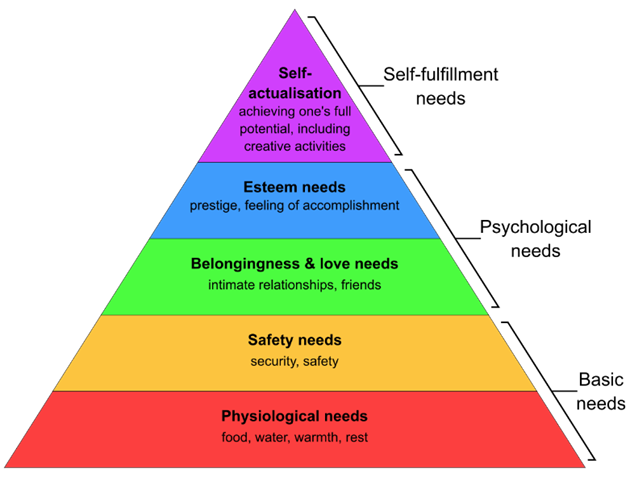

As mentioned above, we are social animals and like all animals we are driven by needs. We know from nearly a century of research that the brain contains specific circuitry that is dedicated to satisfying these needs from the very basic, like breathing and eating, to more abstract and perilous behaviors like searching for just the right gift for one’s spouse. The American psychologist Abraham Maslow conceived of a hierarchy of needs as part of a theory to understand human motivation. This conceptualization divided human needs into three categories: basic needs, psychological needs, and self-fulfillment needs. This is depicted in the figure below.

For the sake of this essay, I will focus only on the psychological needs. One notable feature of his theory is the importance of friends and intimate relationships for psychological well-being. We are motivated to form and maintain friendships because they fulfill the need to be connected to a greater social whole which, according to Maslow, is a necessary component to achieving one’s full potential as a person. That may be true, but aside from a greater goal of self-actualization friendships are also intrinsically rewarding. Social media capitalizes on this phenomenon by constantly reminding its subscribers how may online followers/friends they have. A more tangible instance of reward is the gratitude we feel when a friend pays for a drink or helps us move to a new apartment (an act of true friendship if there ever was one). We also experience reward vicariously when we do something nice for another person, whether they are a friend or a stranger. For example, I am in the habit of opening doors for women*. It’s a simple courtesy that makes me feel good. As mentioned above, our brains are wired for reward. Rewards motivate our every behavior, whether the behavior benefits oneself, is an act of altruism, or an act of friendship. The bottom line is that friendships are rewarding in countless ways and are a seemingly essential part of being human.

*I am aware that some may view this behavior as chauvinist and I have made a concerted effort in recent years to open doors for men as well.

True friends stab you in the front.

-Oscar Wilde

Friendship, Learning and Memory

Two thoughts come to mind when I think about how I have learned from my friends. The first is that I have often sought friendships with those I admire or who have qualities that I aspire to. In part, it is though friendships that we are shaped into the people we become. Friends often set a good example for us to follow. This is learning how to be. This could be how to treat others, how to deal with adversity and success, how to listen, etc. The possibilities for learning in this manner are numerous and often unplanned or unexpected. I have a friend who appropriates my jokes and funny stories for his own use, and then tells me about it later. A shared sense of humor is a powerful bonding agent for a friendship. The point I am trying to make is that the good stuff from our friends rubs off on us (…and sometimes the bad stuff too, but we can blame our friends for that). Friendships change who we are. It is also the power of friendship that can give us a glimpse of ourselves through another’s eyes. This is both affirming and corrective. Friends are sounding boards that let us know how we are doing in both subtle and not-so-subtle ways. Friends encourage and support each other. It is the very best of friends who are unafraid to administer an ego adjustment or tell us when we are wrong. I think the way we learn from our friends differs from learning that occurs by other means, such as from teachers, books, the internet, etc. We don’t often form emotional bonds with people we do not know personally or with the various media sources we consume at alarming rates these days. It’s these deeper emotional bonds that motivate us to listen, to learn, and sometimes to change. I speculate that this type of associative learning is accomplished by the brain in a manner that is somehow different from other types of learning.

A second thought is that, through friendships, we learn an appreciation for things and ways of thinking that did not originate from within ourselves. The interests of our friends become, to some degree, our interests too. Through our friends we develop new passions and sensibilities. Through my friendships, I have developed interests in birding, trees, and tennis, to name just a few. These relationships have also exposed me to the career interests of my friends that I have come to appreciate. For example, I very much doubt that I would ever have been exposed to the finer points of public land use policy, solid rocket motor construction, and endoscopic spine surgery were it not for my friends. These are just a few examples of the universe of things that I have been exposed to through friendships. It is through our friends that we live many lives vicariously and are enriched by the experience.

There may be some truth to the aforementioned movie line “friendship… might be the only thing you never forget”. Think about an important memory from your life. This act of remembering is what psychologists refer to as declarative memory, it is the memory process related to a recollection of facts and events. I really like the word ‘recollection’ in this context because it suggests that the act of retrieving a memory may be a “re-collection” of disparate bits of information to form a familiar narrative event. We know that certain brain regions, such as the hippocampus, play an important role in this process. We also know from our own experience (and many decades of research) that these declarative memories are characterized by specific elements. Now think about that memory again. I’ll bet that your memory of that event contains details about the place, the people, and maybe even the emotions you experienced at that time. These elements seem to provide a framework for supporting our memories in all their seemingly rich detail. These elements, such as places and people are critical for these “re-collections”. There is neuroscientific evidence that the hippocampus contains a dedicated mechanism for remembering spatial information and spatial relationships, suggesting there may indeed be something special about places that is important for anchoring our memories (the discovery of “place cells” in the hippocampus was awarded the Nobel prize in 2014). I would like to suggest that friends may also have a special role in supporting memory. Many of our formative and most profound memories are those that include friends and loved ones. When friends and family gather, they often tell stories about past shared experiences. It may be this shared narrative among friends that anchors us in time and is part of the critical mnemonic framework that enables us to recall our past.

I have been fortunate to have many excellent and long-lasting friendships. I think of these friendships often, although it is becoming increasingly rare that I can be with these friends in person. It is my memory of these friendships that makes me smile and look forward to the next time we are together. Hopefully by then we’ll have that brain thing all figured out.

From left: Gary Lee, Andrew Rossi, Neil Norton, Carlton Stetson

_____________________________________________________