Making friends in my line of work as a community designer is so obvious and natural that sometimes it escapes notice, until a wise old man reminds me to pay attention. Billy asked me to write a piece about friendship and community design and it dawns on me that in most instances, friendship in the community is an integral part of engaging the community in identifying problems, finding alternatives and deciding on solutions, what I call participatory design.

One example is the design of a neighborhood park in a very densely populated district in Taipei. Along with my students from the National Taiwan University, we came upon an abandoned site turned into a neighborhood garbage dump. We discovered that this site is a designated location for a neighborhood park but due to disagreements over its design, it had been vacant for many years without a solution. Two factions of the community were constantly at odds over large and small issues. The students saw an opportunity and took on the challenge of engaging the opposing groups of residents. Initially they established an after-school store-front workshop across the street from the site where school children could come to do their homework tutored by the NTU students. Of course both parents and school children were enthusiastic with this opportunity and after our NTU students had become familiar with all the neighborhood school children, a site cleaning party was organized. The event was planned and carried out by the collaboration of the NTU students and the local school children. The event was a success ending with a neighborhood party on the cleaned site. Because school children from both factions of the neighborhood were actively engaged, their respective family members all came out for the party. All agreed that cleaning out this eyesore was a positive step taken by the community. As a result, previous tensions between opposing factions began to ease.

Following this initial action, NTU students, along with interested local school children, began to plan for the future park. Aware of the differences that existed in the neighborhood, the group had to devise activities that would bring people together, not necessarily to agree, but to engage. One of the first activities was to ask people in the community to identify places which they either like or dislike by the use of instant cameras to record. By soliciting over a hundred responses from old people, young people, housewives and shopkeepers, a photo exhibit of the responses were held on site for all to see. Photos of likes and dislikes were grouped separately and the effect of the display was amazing in that people of opposing factions suddenly realized their values about the qualities of the neighborhood environment are much more similar and close to each other rather than different. People from opposing factions began to talk to each other for the first time, discussing shared opinions and some differing viewpoints. Suddenly, the community seemed to come alive with talk and chatter. They began to find out about each other, about family, about who knows whom, about kids’ schooling, about buying groceries. Small talk about daily life led to friendship across factions and cliques. There was the beginning of a new energy in the community that was previously absent. Along the way the NTU students became friends with the families in the surrounding neighborhood, often being invited home for meals and to serve as big brothers and sisters to the school kids.

At this point NTU students felt that the community was ready to engage in conversations about the future of the park site. Again, activities with school children led the way, including collaborative drawings of an ideal park where two or three kids worked out shared ideas and discarded conflicting proposals. This helped to build trust and mutual reliance which strengthened the friendships in formation. Other activities such as interviews with elderly people were undertaken to gather ideas about the needs and wants of the older generation. For example, one very specific and widely shared idea was that older people like to watch what younger people and kids are doing, rather than being separated and secluded. This became one of the important guidelines to the design of the park.

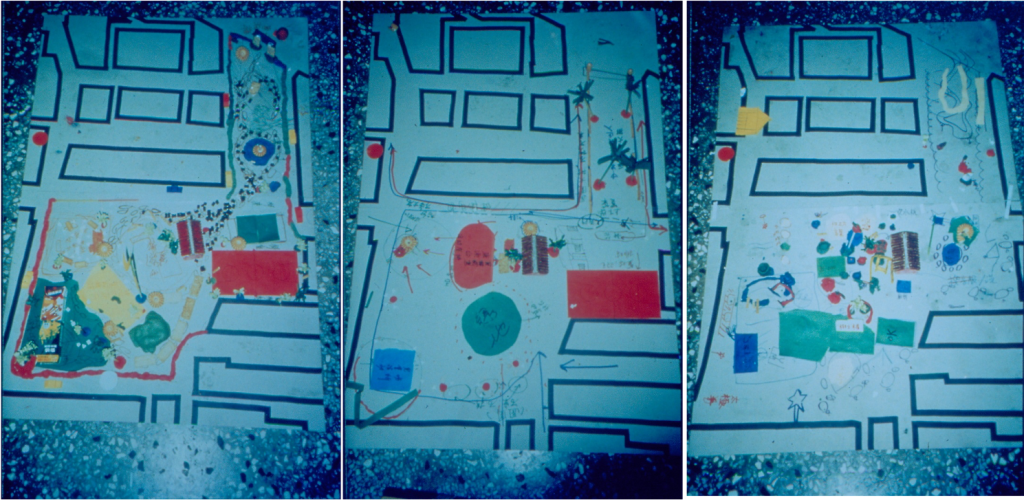

Neighborhood people were then organized into three groups to participate in the actual design of the park. Old people, women and young people formed design teams assisted by the NTU students. Each team proposed a design scheme for the park and a neighborhood preference poll was taken to decide which scheme would be selected.

Unexpectedly some elderly folks objected to counting young people’s votes because they thought that young people are only kids and should not be allowed to participate in serious matters of decision making. Their reasoning was that it is O.K. for young people to make a design proposal, but that the decision should be left to the adults. This sudden turn of events caused confusion among all participants and accusations of procedural shortcomings and age discriminations, etc. began to split the community apart.

At this point the NTU students realized that the impasse between generations would need some time to resolve. A moratorium of two weeks was called on the voting process to relax the tensions. Some way of bringing the community back together needed to be found. By considering the key accomplishment made so far, it was clear that newly formed friendships across factions was a key that could recapture the energy that was waning. For the next two weeks, the NTU students worked with adults and elderly folks to communicate the viewpoint that young people in the neighborhood had contributed responsibly to the process up to this moment and that their proposed design for the park ought to receive equal consideration, and further that the young people’s choices for the preferred design should be respected as any other resident of the neighborhood. Friendship played a critical role as people spent time discussing with family members, with new friends and with elderly people. After two weeks, the neighborhood came together and took a preference poll again, this time with the full inclusion of the young people. A selection of the preferred design was made, to everyone’s satisfaction. With a delay of few weeks, the community gained a new understanding of making group decisions including the pros and cons of direct voting, as well as respect among generations. In addition, some of the details of what makes friendship work were also tested and refined. One such detail is trust, how one person trusts the judgments and values of others.

The NTU students provided the technical support to complete the project and the park was finally realized a year later. In the meantime, the residents of the neighborhood organized a park supervision committee on their own initiative, including maintenance, landscape management, safety patrol, cleaning, and conflict resolution. Bonding with neighbors and making lasting friends through the participatory process of designing the park, a sense of collective achievement was critical in sustaining the supervision committee’s work. At the opening of the park, there was a lot of media exposure of this project and many reporters were curious about what is so special about a participatory design process. The physical aspects of the park seemed ordinary enough, with playground, ball court, seating area, flowers and trees. The design of the park, on first sight, even had some awkward spots that a professional designer would not have done. So the reporters pressed me to explain.

What I said in response was: If you look carefully at what you can see, for example, the long curvilinear bench that ring the edge of the open plaza and ask how it was designed, I would say that the elderly people wanted to see small kids playing in the plaza in a safe and shaded area. The young people’s design proposal incorporated this need and designed a continuous bench which later became one of the most used features of the park. Another example is the ball court where earlier, young people wanted a full size basketball court. When adults and elderly people pointed out that a full size court takes up too much space and some of the elderly people’s needs would have to be disregarded, then the young people, on their own, decided to make only a half court instead of a full court. These kinds of dialog, give and take, among groups and between generations, could only happen is there is trust and mutual respect, and if there is self-awareness and empathy. Then I went on to remind the reporters to ask residents themselves about what is so special about this park. I said you will find what is special may be the non-physical aspects of the park. It is the social process that reversed a community in conflict and turned it into a community in cooperation. The key to this reversal is the building of friendships at the beginning of the process. It is these friendships that let to the sustainability of this park as a loved neighborhood place.

True enough, after more than twenty years since its opening, on a recent visit I found the trees have grown tall as well as the young people who have grown up to become responsible and valuable members of this community. They take pride in creating this community space through the agency of friendship. The park, in turn, provides the context for sustaining robust second generation friendships.

_____________________________________________________

John K.C. Liu is currently the chairman of the Building and Planning Research Foundation (BPRF) at the National Taiwan University, of which he was the founding executive director in 1990. Over the past thirty years the BPRF has provided professional planning and design services to improve the everyday living environment of more than 500 communities. Significant projects include the Yilan Performing Arts Center, Taipei Treasure Hill Historic Village Preservation and Reuse, South-West Coastal Area Ecological Planning, Heritage Planning for the Indigenous Kochapogan settlement , and the Houpi Community Development Planning in Yilan. Specific methodologies of direct community participation have been refined through practice.

John K.C. Liu attended the Rhode Island School of Design from 1963-1965, and in 1968 received a B.Arch.from the Cooper Union in New York. In 1969 he received a M.Arch. from the University of Washington, Seattle and in 1980 a Ph.D. in Architecture from the University of California, Berkeley.

Dr. Liu’s current research and professional interests are in sustainable development and environment planning, ecological design, public facilities planning and design including theaters, museums, schools, housing, and historical heritage planning. His special expertise is in participatory community planning and design.

Dr. Liu has been a Professor in the Graduate Institute of Building and Planning at the National Taiwan University. He has also taught at the University of Washington, Seattle, the Penn State University, Tunghai and Chung Yuan universities in Taiwan, U.C. Berkeley, California, and Tsinghua University, Beijing. During 2016-2017 he was the OSM Distinguished Visiting Professor at National University of Singapore Department of Architecture.

Dr. Liu’s contributions to sustainable community development and planning have been recognized by numerous honors and awards. They include: 16th Taipei Culture Award, 2012; First Prize,Taiwan Architects Association Annual Awards, for the Yilan County Performing Arts Center, 2000; California State Asian American Association of Engineers Professional Achievement Award, 1989; State of California Affordable Housing Award, 1986; U.S. National Science Foundation Public Service Science Residency award, 1981; Progressive Architecture Awards Citation in Applied Research, 1978.

_________________________________________________

BILLY’s COMMENTS : Billy met John in 1967 as volunteers at New York Chinatown. Several young Chinese Architects and Planners formed a Group named New York Chinatown Urban Design Team. We became friends and have kept up ever since. John and wife Shirley have children in the Bay Area. They visit their children regularly and each time they come they would visit Billy and Lucille at Portola Valley – near Stanford University.

_____________________________________________________________