In June 2021, retired architect Billy Lee, a member of USCPFA’s South Bay chapter, published an interesting online essay titled “What Is Friendly Architecture?” Lee’s thesis revolves around a question: “can architecture induce compassion?” He further identifies two layers of compassion: compassionate feelings and compassionate actions. After years of search, he said he had not found “any sample of Inspiring Architecture that can for certain induce compassionate actions.” In the modern world where depersonalization goes under the name of reason and alienation in all its forms prevails, this is a timely and relevant question, and his efforts to identify friendly architecture to address such issues deserves wider attention.

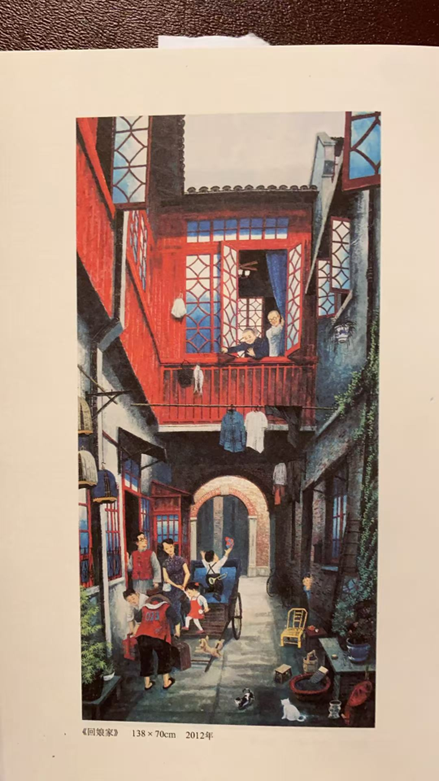

I would argue that Shanghai’s shikumen, a type of hybrid residential architecture, may turn out to be what Lee has been looking for: the kind of “friendly architecture” that induces compassionate actions. Shikumen originated in the indigenous residential buildings common in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River and, through Western-inspired innovations, it evolved into a type of hybrid architecture. During its peak, in the 1940s, it housed more than 70% of Shanghai’s population.

Shikumen resembles traditional Chinese residences in layout and front door design that features a black double door made of heavy wood with a brass ring on each side, often topped by decorative patterns. Meanwhile, it is equipped with modern amenities, such as running water and even gas ranges and sanitation facilities in some varieties, and it appears in contiguous rows—both features recall townhouses in the West.

Shikumen first emerged in Shanghai’s foreign concessions in the mid-19 th century to meet the housing needs for refugees and migrants that came to the city in large numbers. To provide cost- effective homes to suit different budget sizes, architects at the stage of design already entertained the scenario that a shikumen building could be rented to tenants room by room. As well as affordable rent, factors like privacy need, ease of access to rooms, and available communal spaces such as kitchens or bathrooms made sharing a shikumen building possible and even desirable.

However, what made shikumen a “welcome,” “open” architecture type conducive to friendly interaction was ultimately the Chinese traditions shared by occupants. The compact living conditions generally encouraged reciprocal behaviors, from mutual respect to mutual accommodation, from mutual assistance to loving-kind care, all based on traditional values. The goodwill or compassion of shikumen neighbors toward each other began as feelings and then proceeded to actions, as necessitated by practical situations and dictated by shared values as well.

Just as Lee suggests perceptively, once friendly architecture starts the process of friendship and trust building, cultural practices and individual know-how must take over and complete the process. I would add that friendlyarchitecture per se merely provides a physical and environmental possibility, but it takes the occupants’ shared culture to realize its humanist potentials. To put it another way, shikumen as friendly architecture enables shikumen culture, in which the architectural and the cultural elements blend into one social phenomenon.

Shanghai had a high population density. In the 1940s, some districts in the city core reached an incredible density of 250,000 persons per square mile. Shikumen’s high occupancy density reflected the general urban crowding. Shikumen met the massive housing demand, and in the process became a friendly architecture that facilitated friendly exchanges among neighbors living under the same roof.

Recent memoirs of former shikumen residents tell many touching stories about good neighborly relations. A memoirist named Li Mu recalls how, in a child’s eyes, her family got along well with other families share the same three-story shikumen building. Little acts of kindness were performed daily.

For example, she and her siblings kept forgetting their key for the building, but their neighbor always kindly opened the door to let the kids in, without a word of rebuke. Another neighbor, nicknamed Swarthy Aunt was a spare-time seamstress who made clothes for her husband and school-age sons. Seeing Li Mu was envious, Swarthy Aunt offered to make an apron and blouse with lace from scrap cloth for the girl. To return the favor, Li Mu’s mother, a teacher, started to coach the neighbor boys to improve their grades. Li Mu says she not only learned from Swarthy Aunt how to do household chores but also came to be influenced by her positive attitude to life: “Never lose your smile and courage even when you go through tough times.” She realized that a good neighbor matters more than faraway relative.

In Chinese custom, unrelated people are often addressed by appropriate kin terms, such as uncle or aunt, grandpa or grandma, or brother and sister. This practice was continued with shikumen dwellers often with the designation of the room they occupied added to it. For example, neighbors were referred to as Sister-in-law (of the) Front Hall, or Uncle (of the) Ting Zijian (a small room halfway between the first and second floors), or Grandma (of the) Upstairs Backroom. Thus, through its layout, shikumen metaphorically organized the unrelated occupants into a big family.

To put it another way, architectural elements, i.e., the rooms, were assigned individual identities and subsumed under an ethical system based on the family. Indeed, the residents sharing a shikumen unit functioned like a single family due to their circumstances. They would share communal spaces like kitchens, toilets, hallways, and rooftop patios. They would often share a water meter as well, but all would have a stake in keeping the building safe from outside threat and in maintaining internal order.

The family concept helped the residents to handle communal and personal relations in an informal but effective way.

To be sure, life in a space-strapped environment can be challenging, but it also makes co- operation and understanding necessary, precious, and even rewarding. Take the communal kitchen for instance. In a shikumen unit, a communal kitchen was typically shared by two to five families. Each family would occupy a small space for a coal-burning stove or a gas range, and perhaps additional room for a small cupboard as well, while sharing the sink with tap water and sometimes an “island” for food preparation with their neighbors. During dinner time, several families would prepare their dinners simultaneously. Women chatted while cooking. Special dishes of a family would catch the attention of the whole kitchen. During Chinese New Year, Grandma of the upstairs backroom would offer a bowl of sesame dumplings to curious kids. It was not uncommon that people of different regional backgrounds learned to appreciate and even imitate each other’s cuisine. Sharing a sink during meal preparation required a protocol of courtesy and mutual accommodation. Rules for usage of communal spaces and facilities were mostly based on unwritten, tacit understanding of what was reasonable and appropriate under the given circumstances.

Shikumen culture was a migrant culture derived from traditional Chinese culture. The collectivist orientation of traditional Chinese culture once relied heavily on the kinship system and/or shared local identity to work. Migrants from all over the country, now cut off from their old ties, found themselves in an unfamiliar urban environment, isolated and helpless. To alleviate this problem, shikumen played a role as friendly architecture. Shikumen units provided not just a place to live but also a social space for its occupants to continue to practice their cultural values such as Confucian benevolence, easy-going manners as advocated by Daoists, and mercy and resignation to fate taught by Buddhism. Applying kinship terms to address neighbors was not a simple act of courtesy; it made shikumen feel like a big family, a clan, or a miniature village. In short, it represents a cultural reconstitution. This was the fundamental reason why shikumen may be regarded as a typical friendly architecture.

—————————————————————————————————————————

*I wish to thank Mr. Billy Lee for inspiring this essay and an extended article on shikumen in the US-China Review. I would not have done the writing without his consistent encouragement and support.

Sheng-Tai Chang received his Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from the University of Southern California (USC). He also holds an M.A. in English from the University of Calgary in Canada and a second M.A. in Asian Languages and cultures from USC. In addition to writing, his areas of interest include American literature, Chinese literature, and East Asian humanities. He has published scholarly articles and translations of Asian and Asian-American writers. He regularly teaches various courses in composition, literature, and humanities.

______________________________________________________________________________________________