This subject is so broad and deep that the most I can hope to do is to stimulate the readers to explore on their own, afterwards. I myself did some research and learned from many sources. I found that Internet search with Chinese characters trailed with “in English” can bring up articles which may be helpful to people who cannot read Chinese. As both traditional characters and simplified characters are encountered in book and articles, I showed both versions in the title, but for the rest of the article, I will use only the traditional characters

Let me begin with recounting my mental journey in the last few days after Bill asked me to write on this subject.

From my personal understanding of the word Yi and the words Yi Qi, I knew they were related but not identical. Yi is clearly a Virtue and the closest English translation that comes to my mind is Righteousness. Yi Qi is like a code of conduct between friends or the force/energy leading to such behavior. The closest English words for that behavior are loyalty and comradeship. Intuitively, we associate a Virtue with goodness in its particular aspect, within which it is often considered mandatory. How often do we hear someone say Righteousness is optional? But we know that acting loyally for a friend may not always be the righteous thing to do. This is the reason why Yi is called the 大義, the big righteousness, and Yi Qi is called the 小義, the small righteousness. Strictly speaking, Thus Yi Qi is not the same as Yi but they are definitely related.

The traditional character of 義 is made up of the character for sheep 羊 on top of the character for I 我. An interpretation of this combination is that a sheep stands for kindness. Combined with “I”, kindness from myself to others is Yi. This is only from the perspective of the origin of the word.

The philosophical and scholarly meaning of the word 義 traces back to Confucianism. In fact, more to Mencius (372-289 BC) than Confucius (551-479 BC). Mencius was a fourth generation disciple of Confucianism. They lived during the historical period called Spring and Autumn, from 770 to 476 BC, after the Zhou dynasty and before the Warring States period from 475 to 221 BC. During these two periods, China was divided and wars were frequent and common.

The highest Virtue according to Confucius is Ren 仁. It is translated as Benevolence in English. The word is made up of two parts. Human or 人 on the left and Two or 二 on the right. It indicates the relationship or behavior between two human beings.

Confucius never defined Ren with a single all-encompassing description. He answered different questions about Ren in different perspectives or aspects. To learn about Ren by reading Confucius’ Analects is like listening to many blind men describing an elephant after touching it and concluding what an elephant is. (My analogy should be taken only as a metaphor and not meant to be derogatory.) It states that holistic knowledge is derived from many observations from different perspectives which involve parts of the whole. Trying to grasp the whole at one attempt risks leaving some important parts out. It is also for this reason that learning is a life-long journey – it takes years of observations and learning to form a better and more complete understanding.

Before I go on, I would like to point out that the single-character-based Chinese language has a systemic advantage over multisyllabic languages in fostering rapid retrieval of thoughts or concepts through the power of association and memorization.

When another word is added before or after a word, that pair of words become a potential extension of the meaning of both words.

For example, the pair of words Ren (仁) and Ai (爱) which means Love often are used together. So Ren takes on the meaning of “Love for others” as well. 仁慈(Ren Ci) is another common memory association adding Kindliness to the meaning of Ren.

Likewise a common pairing is Ren Yi (仁義) which automatically brings Yi out, not as an extension of the meaning of Ren but an ordered pair of two Virtues, Benevolence and Righteousness, ranking Ren before Yi.

Along the same logic of association, the pairing of Yi and Qi thus expands the thought on Yi to Yi Qi, creating interest on the second and both topics!

While on this track of thoughts, Chinese proverbs are commonly made up of four characters. They are easy to memorize visually and by sound, by the literate as well as the illiterate. Quoting a proverb is often a way to justify the validity of a personal opinion. It is as if a proverb is an authority of truth.

Plain words by themselves are not as powerful as words that have a historical or moral story behind them. In other words, there is often a moral to the story. Parents use their favorite proverbs to teach the behavior of their children either consciously or unconsciously by way of their habitual language.

But alas, popular culture also creates catchy four-character good sounding words which look and feel like classical proverbs. Titles of popular movies and drama series have become sources of sound-alike proverbs. But I digressed. My mind is wandering into modern day Artificial Intelligence algorithms which are trained on massive data so that an answer is popped out when presented with an input. Our real mind works like that too! It has accumulated a big data set of words and ideas connected by association, preselected by our personal confirmation bias. I wonder, “Is this related to the concept of Qi?” Is that an explanation for the motive force beneath 義氣?

I brought up two-character and four-character groupings. What about three and five? Three-character hymn (or doctrine) 三字經 (San Zi Jing) was a classical and traditional “teaching tool” for children’s memorization. It starts with “人之初, 性本善” meaning “At humans’ beginning, their nature is originally good.” This shows the influence of Mencius on Chinese culture. On a side note, San Zi Jing is also used as a widely known euphemism for swear words and foul language, at least in the popular culture of Hong Kong.

Coming back to Mencius’ teaching on Yi, the first chapter of the Works of Mencius, “King Hui of Liang, Part I” 梁惠王章句上, recounted that Mencius went to see King Hui of Liang and the king asked for counsels to profit his kingdom. Mencius replied, “Why profits? My counsels are benevolence and righteousness. If your Majesty asks to profit your kingdom, the officials will ask to profit their families. The common people will ask to profit their persons… Superiors and inferiors will try to snatch profit one from the other and the kingdom will be endangered… If righteousness be put last, and profit be put first, they will not be satisfied without snatching all. There never has been a benevolent man who neglected his parents. There never has been a righteous man who made his sovereign an after consideration. Let your majesty also say Benevolence and Righteousness and let these be your only themes. Why must you use that word Profit?” [Paraphrased and abbreviated from James Legge translation.]

From this opening chapter of the Work of Mencius, it is clear that he continued the Confucius emphasis on both Benevolence and Righteousness. Where he started to be more practical for his contemporary period of more wars and disorders is his approach of emphasizing the utility of advocating Yi.

Extending his teaching, Mencius brought out the four 端 Duan, Ren Yi Li Zi 仁義禮智, translated as principles or limbs by Legge and loosely interpretable as beginning. I take my liberty and use “beginning” — “The feeling of commiseration is the beginning of benevolence Ren 仁. The feeling of shame and dislike 廉耻 is the beginning of righteousness Yi義. The feeling of modesty and complaisance is the beginning of propriety Li禮. The feeling of approving and disapproving is the beginning of knowledge Zi 智.

The key point is that a common human feeling of shame and dislike was pointed out as a starting force of Righteousness.

Before letting the number Four get too much weight in our brains, I hasten to point out that there are slightly different lists of virtues in Confucianism or Chinese culture.

One list of Five adds Xin 信 or Trust. This list is called Five Constant Virtues, 五常: 仁義禮智信.

Due to the strong sense of relationships and hierarchical structure of the Chinese society, Chinese have very clear awareness of the proper behavior between the five relationships – King and officials, father and son, big brother and young brother, husband and wife, and between friends.

Governing the first two relationships, the Virtues of Loyalty忠and Filial Piety 孝became prominent. They fitted very well into the feudal society of China lasting almost two thousand years. It should be noted that Loyalty to the King 忠 is a different Chinese virtue than Loyalty to friends義氣.

With the revolution led by Sun Yat Sen in 1911, Western values got added to the traditional virtues. The list of 8 advocated in his writing consisted of Loyalty 忠, Filial Piety孝, Benevolence 仁, Love 爱, Trust 信, Righteousness 義, Harmony 和, and Equality 平. These eight words became commonly quoted.

Before discussing about Yi Qi or Loyalty to friends, I would like to look up and look broader. Confucianism is human centric. Not a religion nor a complete cosmic view. In the many Chinese traditions, a single personal God is not postulated nor declared by faith. An impersonal Heaven with mandate given to a righteous King is the basis of the Chinese civil society. Lao Tzu 老子 is recognized as the philosopher who taught about Dao 道 as the universal Oneness. He is thought to be a senior contemporary of Confucius. His Dao De Jing 道德經 is well known. Chapter 38 includes the following passage.

“Thus it was that when the Tâo was lost, its attributes appeared; when its attributes were lost, benevolence appeared; when benevolence was lost, righteousness appeared; and when righteousness was lost, the proprieties appeared.”

If you would take this chain of reasoning further, would you say “when the proprieties were lost, legalism appeared?”

One may further say “when legalism is lost, 義氣 Yi Qi appears!”

With that, looking to the West and the world, we can understand why Fundamentalism or “reversing the trend of deterioration to the good old days” is such an attractive idea. Sorry, I digressed again.

It is true though that after legalism was added to Chinese culture and developed into Chinese government systems and societal norms, personal survival still required making choices and facing the consequences. The circle comes back to “what profits me?” when making the choice. And not only profits but penalties or losses.

After traveling a mental road on Yi or Righteousness, it is time for me to take up popular culture in a historical journey for understanding Yi Qi.

If King Arthur with his knights of the round table is a popular hero standing for Western virtues of chivalry, loyalty and brotherhood, etc., then Guan Yu 關羽, Guan Gong 關公 or Guan Di 關帝 (emperor or god) is the Chinese folk hero who stands for loyalty to fraternity. There are other historical or fictional heroes of course, but because Guan Yu is almost considered and worshipped as a deity by Chinese, especially when they emigrated to the diaspora, his influence on the Chinese people overseas, including the merchant associations and underground organizations, was significant.

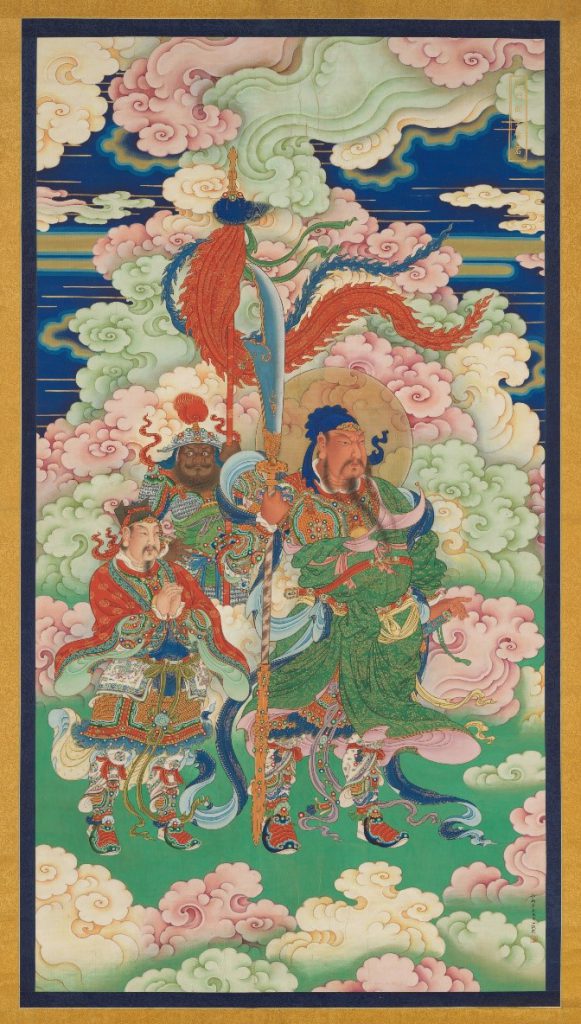

[Picture source: Metropolitan Museum, public domain.}

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/62002

To illustrate this, I tried to search for Chinese temples which exalt Guan Gong in the US, but failed to find a prominent one. But I found a website of the Guan Di Temple in the Yokohama Chinatown. It is a good source on the history of that temple, showing the importance of it to the Chinese immigrants in Yokohama. https://yokohama-kanteibyo.com/en/

Guan Yu is usually portrayed as a warrior or general with a red face and a long beard, carrying a heavy and long single-edged crescent-shaped weapon. He is known for his loyalty to the oath he took with Liu Bei and Zhang Fei in a cherry blossom garden. Upon capture by their military and political opponent, he refused to disavow his oath.

This form of fraternal loyalty does not break any moral or legal norms. So it exhibits both Righteousness and Fraternal Loyalty. Noted is the historical period of this legend, about 200 AD, the end of the East Han Dynasty.

Cover of Comic Book depicting the heroes of Water Margin.

Moving into grey areas of morality is the popular stories of the “Water Margin: Outlaws of the Marsh” 水浒传. Several English versions are available in book or electronic forms. This very popular folks novel was considered by scholars as written in the Ming dynasty about 1500 AD but the stories referred to a group of outlaws who got together to fight against the corrupted authorities in the Song dynasty. So it is possible that these folk legends were passed down from that time, through story telling. In any case, story telling was a popular entertainment. These stories were very influential on the education and cultural behavior of the common people. The code of conduct of these heroes defying law enforcement in being loyal to one another and performing charitable deeds to the poor underclass was exalted as Yi Qi. Fraternal loyalty is raised above obeying unjust laws or officials.

However, the stories are not so black and white. They portrayed those folk heroes as humans with flaws. The ideal code of conduct is one thing but actual behavior was full of contradictions. Most people though, remembered the Yi Qi parts about their heroes.

To describe the ideal code of conduct, we can read Chapter 71. I will attempt to give an English translation as follows:

“原来泊子里好汉,但闲便下山,或带人马,或只是数个头领,各自取路去。

The good men in the camp, would go down the mountain, bringing their men and horses or with several leaders, going different ways.

途次中若是客商车辆人马,任从经过;若是上任官员,箱里搜出金银来时,全家不留。所得之物解送山寨,纳库公用;其馀些小就便分了。

If on the way they encounter carriages and horses of passengers or merchants, they let them pass freely. If an official going to his new post, and the boxes are found to contain gold or silver, the whole family is not retained and all the possessions are taken to the camp treasury for community use. Small items would be divided.

折莫便是百十里、三二百里,若有钱财广积害民的大户,便引人去公然搬取上山。谁敢阻当!

Within 110 miles and as far as 2-300 miles, if there is a rich and big family which harms the people, they would lead people to openly fetch and move their possessions to the camp. Who dare to stop them?

但打听得有那欺压良善暴富小人,积攒得些家私,不论远近,令人便去尽数收拾上山。如此之为大小何止千百馀处。为是无人可以当抵,又不怕你叫起撞天屈来,因此不曾显露,所以无有说话.

If they hear about those suddenly rich people who bully the meek and the good people and accumulated richness, no matter how far away, they would send people to bring as much as possible to the camp. This they achieved in hundreds to a thousand places. No one could stop them. They do not fear complaints to the officials. Thus their deeds are not noticed and there is nothing to say.

For our Western friends, doesn’t this behavior remind you of Robin Hood and his Merry Men? So, you may ask, what is different about Chinese 義氣?

I would suggest that it is the large number of stories illustrating how these heroes act in response to their friendship and loyalty to one another. Using proverbs as evidence, the following common proverbs are just some of the data planted on Chinese brains which inspire 義氣:

路见不平, 拔刀相助 Encountering injustice on the road, pull a sword to help.

仗义疏财 Give money extensively to uphold righteousness

慷慨仗义 Be generous to uphold righteousness

舍生取义 Give up life to obtain righteousness

兩肋插刀 忠肝義膽 肝腦塗地 Stabbed on ribs in both sides; loyal liver and righteous gall; liver and brain smear the ground.

I would also suggest that it is the degree of its elevation as the most important virtue for friends living in the 江湖, literally river and lake, but meaning people like those heroes in the Marshes or Water Margins. Another image is the piers and the docks where laborers work. Extending the classification from dock laborers, we have the poor workers who emigrated to foreign lands to work and send money back home.

Over the centuries, waves of these laborers went overseas to strange lands of different languages and customs. To survive, they stayed close to one another and helped each other out by forming associations, usually according to their regions of origin or family names. Temples and community associations became gathering places. Statues of Guan Gong or other deities were objects of reverence or prayers. Some societies had their codes of honor and oaths of loyalty. The Virtue of Loyalty to friends was greatly valued because it provided a sense of trust and solidarity.

To use the tool of association again, a popular pair of Chinese words is 侠義 Xia Yi. The best translation of 侠 if treated as a noun is a heroic martial artist. Kung Fu movies are translated from the Chinese words 武侠片. Therefore when Chinese hear the words 義氣, memories of heroes in Kung Fu movies come up.

In my mind, because of my age and background, Kung Fu is associated with Bruce Lee. “The Big Boss” was his first Kung Fu movie seen in the US in 1971 and its background was about Chinese laborers in SE Asia banding together to fight against their employer who was a local big boss with a gang. The Chinese workers showed their 義氣 to one another and fought bravely against them.

After Bruce Lee passed away, Kung Fu movies starring Jackie Chan and Jet Li were very popular in both the East and the West. Recognize though, the frequency and duration of exposure to this genre of popular movies and drama series were ten times greater on Chinese viewers because most of those works were not exported for Western viewers.

Another noteworthy Kung Fu movie well known to the West was made by Li An twenty years ago, “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon”. Recently this movie was quoted in a speech.

In the movie, someone said to a martial arts master, “It must be exciting to walk the world, to be totally free!” The master replied, “But there are rules too: amity, credibility, integrity.”

At this point of my mind-to-finger journey, I am stuck and hesitating. I reminded myself of being one of many blind men surrounding an elephant, describing it from only a limited viewpoint at a time. Then I realized that there is not enough depth though there is some breadth in what I have written.

For more depth, I would encourage reading about Guan Yu and some of the stories in the Water Margin to get some details about what kind of behavior is considered as loyalty between friends. Interpreting the details in Western traditions, one will likely recognize the same values and the same challenges in making personal choices between conflicting values when friendship is involved. Hopefully, from these tradeoffs and dilemma, we all recognize the common human nature and meaning of life.

Winding up my mental journey, I found this survey result on the Internet dated July 2020:

https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/lifestyle/2020/07/top-traits-which-make-up-a-good-friend-revealed-in-new-study.html “Loyalty is the top trait of a best friend, a new study has found.”

“To mark International Friendship Day on July 30, UK researchers have determined which qualities are needed to maintain a lasting friendship.

The poll revealed that 79 percent of people wanted a loyal friend, with someone who is trustworthy claiming second place with 66 percent.”

In my mind, I believe that human values are universal regardless of cultural differences. Relative priorities may vary because of the ways individuals are brought up in their environments, under the influence of culture and education. But definitely, we can learn more about ourselves by explaining our culture to other people and then realize that we share common values.

Something new I have learned in writing this piece is that two thousand five hundred years after Confucius, I realize that I still have much to learn after reaching 70 years of age. I would attribute this to the addition of 2500 years of history, expansion of human interaction from one country to the whole world, and advancement of knowledge in science and technology. At least three orders of magnitude bigger and deeper!

I would hope to continue learning for 30 more years!

POSTSCRIPT From Yang to Yin

My better half always provides me with challenging and stimulating feedback. With one sentence she woke me up. “Yi Qi is not a dominant vocabulary in the female mindset. Not betraying personal secrets in close friendship is more important.” This explains why GUI MI 閨密 (secret) or 閨蜜 (honey) is a popular contemporary term used by women to refer to their closest female friend. Keeping personal secrets is a code of behavior expected between close female friends. It is a more frequent manifestation of Loyalty among female friends.

Her remarks brought up a new image in my mind. My analogy of blind men around an elephant included only men and not women! I had not walked to the other side of the elephant to see the women there, both blind and not. I am the really blind one. Haha!

Extending this though, not only is “holistic” inclusive of female and male, it should include both my left brain and my right brain! Where are the feelings and the beauties of Righteousness and Loyalty?

Alas, my journey so far is still not broad enough!

Bill, you still have more work to do! Sorry!

__________________________________________________________